The term innovation has been making its way into the names of centers for teaching and learning, job descriptions, and the broader discourse on learning in higher education.

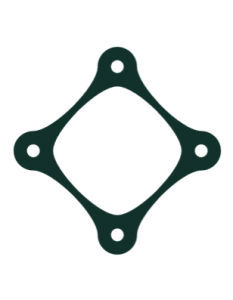

Gathering around a table at the POD Network’s 2019 annual conference, our working group dove into a working definition of learning innovation. I seeded this conversation with a model that has emerged through conversations I have had recently with several colleagues working in the “learning innovation space.” Thanks to Mathew L. Ouellett of Cornell University’s Center for Teaching Innovation and Rachel Niemer, Director, Outreach and Access at the University of Michigan’s Center for Academic Innovation for these rich and fruitful conversations resulting in the Four Spheres of Learning Innovation.

The Four Spheres Model

| I: Methods, practices, or ideas that are new to the individual. G: Methods, practices, or ideas that are new to a group (colleagues, teams, departments, centers). These could include those established in one area of the institution that are adapted to a new context. C: Methods, practices, or ideas that are new to the community/ institution, but may be adapted from other institutions. W: Methods, practices, or ideas that are new to the world |

I recently presented this model to colleagues at my own institution and wanted to draw in some examples that might ground this theory in some practice.

Theory to Praxis

C Programming with Linux Professional Certificate I, C, W

This is a joint project between Dartmouth and Institut Mines-Télécom (IMT), a consortium of public engineering and management universities in France. The program consists of a seven-course series leading to a professional certificate on edX. Building on Dartmouth’s partnership with edX to offer open online courses from Dartmouth faculty from across the arts and sciences and professional schools, this was the first program collaboration between two edX partners. This required cross-cultural, technical, data, financial, and legal capabilities. Working with Thayer Professor Petra Bonfert-Taylor, a project proposal was funded through the support of the Dean’s office; Dartmouth Center for the Advancement of Learning; Information, Technology, and Consulting; IMT; and an external grant.

In addition to over 165,000 enrollments to date, this project provided opportunities for Dartmouth undergraduates to collaborate as members of the course team and introduced a groundbreaking model for learning to code through new webtools. The program has been selected as a finalist for the 2019 edX Prize for Innovative Teaching.

Through a collaboration with learning science experts from Stanford and Cornell, the program has conducted research resulting in a paper, Welcome to the Course: Early Social Cues Influence Women’s Persistence in Computer Science, currently under peer review for CHI 2020 (Human-Computer Interaction conference).

DELTA Summit I, G, C, W

In the summer of 2018, Dartmouth partnered with the National Society for Experiential Education to convene the inaugural DELTA Summit: an applied, reflective professional development program in the theory and practice of experiential learning pedagogy.

The 2018 cohort included 60 educators representing 4 countries, 22 states, 50 colleges and universities, 8 K-12 schools, and 10 independent education organizations. The DELTA leadership team was awarded the 2018 Lone Pine Excellence Award for Innovation.

Classroom Design and Redesign G, C

In 2015, Dartmouth opened the Berry Innovation Classroom, which was designed to provide a flexible learning space to support active learning pedagogies within a technology-enriched environment. A cohort of faculty engaged in the design and use of new classrooms to explore methods in their own teaching and inform the design of subsequent classroom redesign projects.

In working with the faculty Classroom Committee, a survey of all teaching faculty (2018) provided a benchmark of teaching activities and the growing need for more flexible and accessible learning spaces on this historic campus. Working in conjunction with campus planners, technologists, facilities, classroom schedulers, and faculty, we endeavor to provided first-class physical and digital learning spaces to advance the teaching, learning, and research missions of the College.

Reflective Video in Foreign Language Media Course I, C

Students experienced German language and culture using a new learning management system (at the time – Canvas) and a video platform (Zaption – now defunct) to produce their own short video documentaries in the German. The professor and I screened one student film and co-presented this collaborative case of experiential and technology-enhanced learning to the Trustees of Dartmouth College in spring 2014.

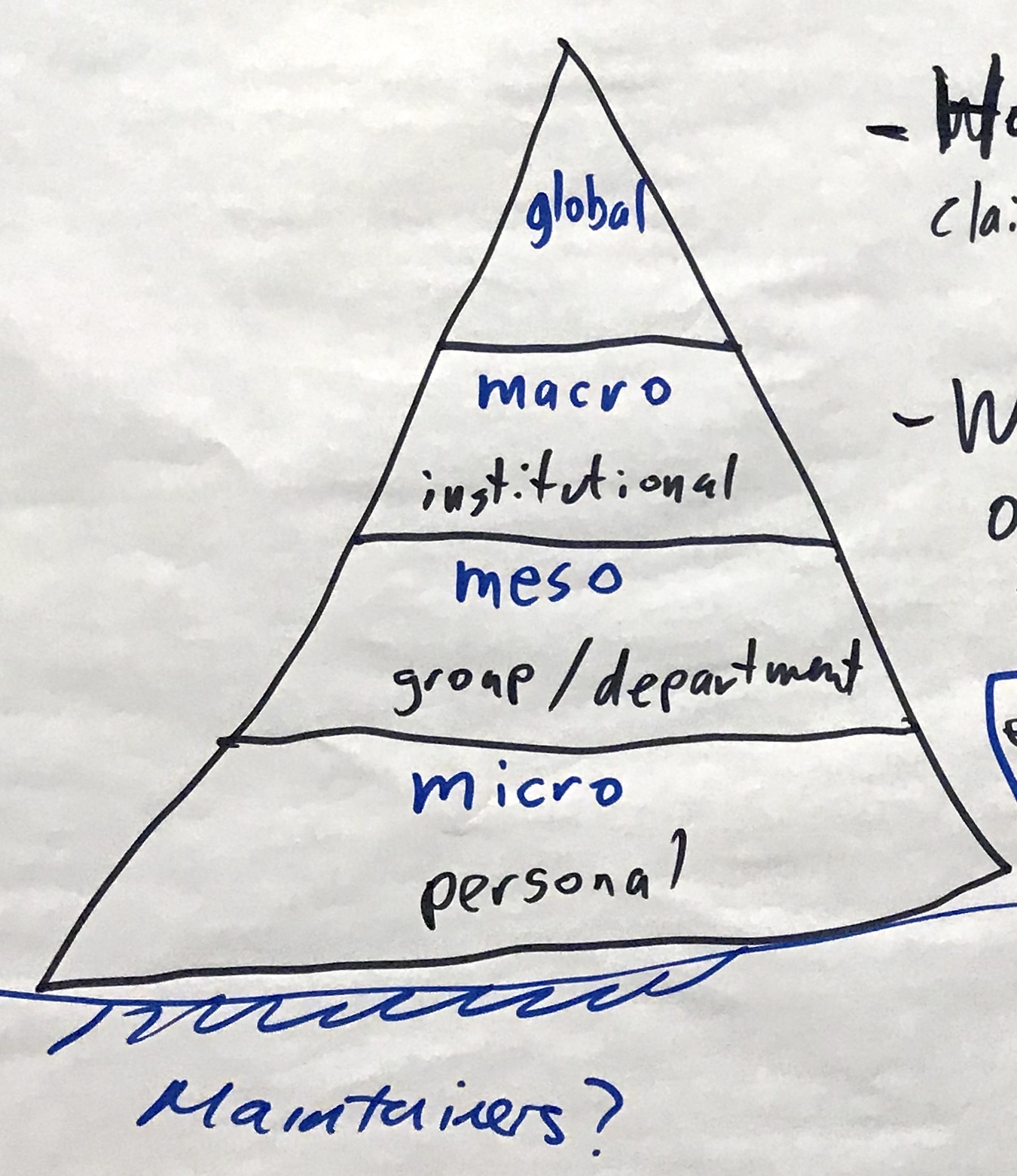

Introducing the Learning Innovation Pyramid

Our POD working group took in this four spheres model and then iterated a bit with …. a pyramid! Educational developers love a Bloom’s Taxonomy-esque model of innovation!

Critical Questions

In exploring this revised model of the learning innovation levels several questions emerged about learning innovation on our campuses.

What is the role of the “the maintainers” in innovation? For example, if you don’t have the basic functionality of stocked markers, you can’t draw a model of innovation. Who stocks the markers? What is the balance of maintaining and innovating? By the way a higher ed movement called The Maintainers have been digging into this on their blog and at their own conference.

How can (if they should at all) centers for teaching and learning (CTLs) claim the learning innovation space? Innovation often evokes examples of digital and technological innovations, however according to the above model, innovation is at its basic level, making change. Rachel Niemer asks, “Should CTL’s claim the innovation space? In what institutional contexts is it beneficial to have CTL’s be the hub of innovation and in what contexts is it detrimental/orthogonal to mission to claim the innovation space?”

So there is more work to do and perhaps we need yet another model of the balance of innovating and maintaining.

![4 quadrants created by a vertical line and a horizontal line, each of which has an arrow on each end Vertical line Top: Institutional. Bottom: Individual. Horizontal line Left: Steady State. Right: Continuous Improvement. Upper right quadrant (Institutional/Continuous Improvement): MicroMasters/MasterTrackCertificate (c.2015)-U-M. Foundational/Gateway Course Initiatives (U-M c.2017). MOOCs (c.2013) - D [wavy dotted line down to lower right quadrant (Continuous Improvement/Individual) MOOCs (c.2019) - D. Online Programs (MOOCs) - Inst. Collab. (c.2011) - D. Gateway Course Redesign (c.2014) - D. [wavy line running from lower left quadrant (Steady State/Individual) MOOCs (c.2012) - U-M up through upper left quadrant (Steady State/Institutional)] to MOOCs (c.2019) - U-M. Lower right quadrant (Continuous Improvement/Individual): Course (Multi-Section) Redesign - D. Course Redesign - D.](https://er.educause.edu/-/media/images/blogs/2019/6/er192307figure1.jpg?hash=A6D59BCF757D68984A6346DE43EE2B268BDB6BB4&la=en)